“There are a finite number of ways to hit a target, and an infinite number of ways to miss it.”

Gary Chapin

By Gary Chapin

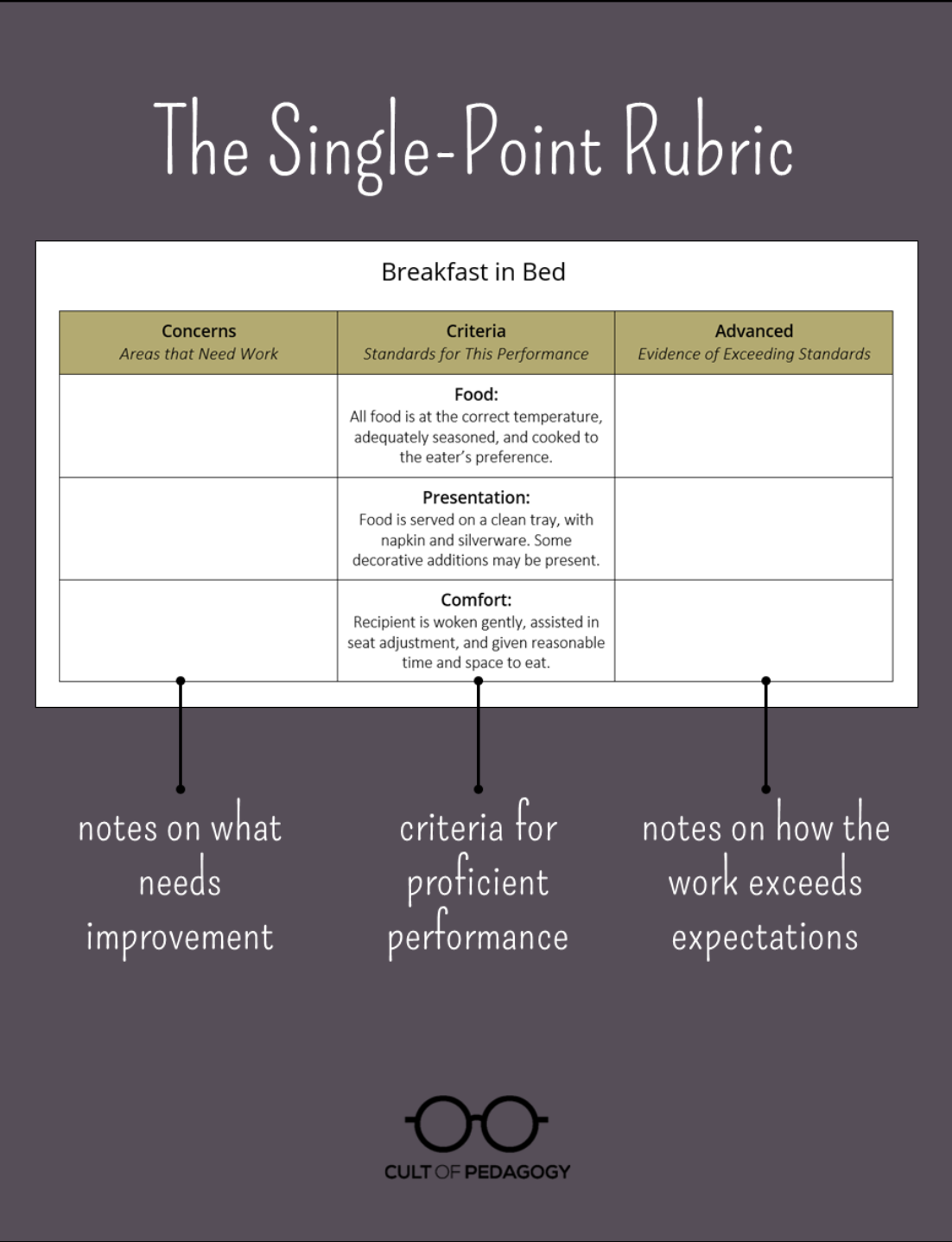

Thanks to a twitter reference some months ago I read a piece by Jennifer Gonzalez over on her wonderful blog, Cult of Pedagogy. Called Meet the #SinglePointRubric, the article made me think, “Where have you been all my life?”

The “points” of a rubric are the columns -- levels of achievement. A four-point rubric typically has some version of meets, doesn’t meet, partially meets, and exceeds. A two-point rubric might have pass and fail (or got it and don’t got it). The single-point rubric has one point, a thing of beauty, a wonder to behold. In the center – the point – is the criteria (the learning target). To the left a space for concerns and ways to improve. To the right, ways in which the work exceeds expectations.

I’ve been doing a LOT of thinking about rubrics over the years. Since at least 2005, there’s been a sort of orthodoxy around the four-point rubric – an orthodoxy that I have encouraged. Most of the resistance to the four-point rubric comes from folks who want more points, so that they can further parse and sort their students’ performance.

Lately, though, I have come to the conclusion that even four points are too many. When filling in the columns indicating what proficiency does not look like, I have felt genuinely inauthentic, sometimes dishonest, and usually unhelpful. The problem is illustrated in the graphic below.

There are a finite number of ways to hit a target, and an infinite number of ways to miss it. Most of the ways-of-missing can teach you something about hitting the target (thus you can consider them “approaching”), but each way-of-missing will also be a unique blend of student’s background and context, reaction to instruction, conditions of assessment, the Earth’s curvature at various latitudes, and the direction of the wind. (Those last two are a joke, but you get my point …) What is the advantage of trying to predict the many ways idealized students might fail? Why write an almost meets or does not meet? Rather, we should be coaching students along the way, setting clear expectations, and responding to their actual performance.

Some argue that the does not meet or partially meets are places to express learning pathways. As if to say, a student will move through the ways-of-missing (now called beginning and developing) to proficiency, that it is a natural path. The error in this way of thinking is that learning pathways are tools for instruction and planning. They are prescriptive (and predictive).

The function of a rubric is descriptive. The most important single thing a rubric can do is to describe what success looks like in a way that informs and inspires a student’s performance. Other uses of the rubric – students planning their approach to the target, peer evaluation, and revisions – all grow from that single priority. And all can be more effectively done in a student-centered learning environment with a single-point rubric as described by Gonzalez. The target is clear, and the blank spaces for “concerns” and “exceeds” allow the actual story of the actual student to be written into the rubric – rather than our expectations of how the “typical” student might partially meet or not meet criteria.

We have been using the four-point rubric with nearly religious consistency for more than a dozen years. Time has passed. Revisiting the idea of the rubric to see how well it has worked and how it can better serve our students is a legitimate and worthwhile exercise. It’s a conversation we should all be having.